2GP.1 Make-or-Buy

2GP.1.E1

At a university in the United States, an accounting department has assigned the tenured Professor Golightly to teach the Introduction to Managerial Accounting class. This class is a crucial input to the department’s eventual output, accounting major graduates. Professor Golightly earns $30,000 for teaching three sections of this class during the semester. The accounting department has a differentiation strategy of attracting new students to the major with quality teaching. Professor Golightly is considered a high-quality teacher.

The university is considering re-assigning Professor Golightly to a different set of classes and hiring adjunct professors to teach the Introduction to Managerial Accounting class. Adjunct professors are paid the equivalent of $5,000 per section they teach. Professor Golightly’s new assignment would be to teach four sections of the upper division of cost accounting (no difference in how much the professor earns). These sections are currently taught by four adjunct professors (paid at $5,000 as well).

Required

(A) According to relevant cost analysis, how much money will the accounting department gain or lose by re-assigning Professor Golightly?

(B) According to strategic cost analysis, should the department re-assign Professor Golightly?

Answer (A)

A) Relevant cost analysis compares two or more alternatives. The two alternatives are (1) the current status quo and (2) reassigning the professor. We have no data suggesting revenue for the department would change between the two alternatives so we will just be comparing costs.

(Alternative 1 is “making” the introductory classes and “buying” the advanced classes, whereas Alternative 2 is “buying” the introductory classes and “making” the advanced classes.)

Alternative 1 costs: $30,000 professor salary + 4 * 5,000 adjunct salary = $50,000.

Alternative 2 costs: $30,000 professor salary + 3 * $5,000 adjunct salary = $45,000.

Alternative 2’s costs are $5,000 lower, thus it brings in $5,000 more in profit and is the better alternative (from a relevant cost analysis perspective).

Answer (B)

B) Strategic cost analysis considers additional costs that might be more long-term or qualitative and thus harder to account for with traditional relevant cost analysis. The strategic issue here is how much good the professor does for the department’s strategy by teaching the introductory classes versus the alternative. The department is trying to differentiate itself for pre-major students (that’s its chosen strategy). Having this favorite professor teach some of the earliest classes in the program seems to support that strategy.

The alternative is to have adjuncts replace the professor and test whether they are as effective at differentiating and selling the major to new students. This seems relatively unlikely. Even if the department hires an adjunct who does an excellent job of this, there are three adjuncts replacing the professor and adjuncts are likely to have higher turnover than tenured professors. This suggests greater variability in quality differentiation from semester to semester. (One might reasonably object to this assumption. I would agree that if the university has an especially deep, committed, and experienced pool of adjunct professors, the assumption likely would not hold.)

In general, then, strategic cost analysis suggests the department should not reassign the professor because this runs counter to the department’s strategy. The department will have to weigh the long-term downside of reassigning the professor against the money it would save by such a reassignment (see the answer to A above). Without knowing more about the scenario, $5,000 savings is probably too small to justify this counter-strategy move.

2GP.1.M1

For several years a firm has bought specialized industrial paint from a supplier that also provides many other inputs the firm uses for its final product. The firm is now looking into making this paint in-house. The paint is purchased for $5 per gallon and 50,000 gallons of paint are required per period.

Making the paint would require the firm to lease equipment for $20,000 per period and buy raw materials at a cost of $0.50 per gallon of paint produced. Two new workers would need to be hired, and each would be paid $20,000 per period. Two current workers would need to be re-assigned from working on the firm’s final product to working on producing the paint. This would decrease the number of final products that could be produced per period by 150 units per period (final products earn $1,000 in profit per unit).

Required

(A) According to relevant cost analysis, how much money will the firm gain or lose if it made the paint

(B) According to strategic cost analysis, should the firm make or buy the paint?

Answer (A)

Alternative 1 is to continue buying the paint. Alternative 2 is to make the paint. There is no indication that paint quality will differ significantly and make revenues different between the two options. Thus we are once again looking just at cost differences between the two alternatives.

Alternative 1 costs: $5 per gallon * 50,000 gallons = $250,000

Alternative 2 costs: $20,000 lease cost + $0.50 raw material cost per gallon * 50,000 gallons + 2 * $20,000 new worker wages + 150 * $1,000 = $235,000

Relevant cost analysis suggests the firm should make the paint because it costs $15,000 less.

Answer (B)

There is little information given about the firm’s strategic situation and aims. The main thing we know of a strategic nature is that this supplier provides a lot of the firm’s inputs. From a value chain perspective, this fact favors continuing to buy paint from this supplier instead of making it in-house.

That’s because continuing to buy from the supplier should help maintain or even advance the relationship between the two firms. It will also help ensure the supplier continues to be financially capable of ably supplying the firm with its other inputs. This could be an issue worth bringing up with the supplier directly. Perhaps the two firms can agree upon a discount on paint that closes some of the

2GP.2 Sell-or-Process-Further

2GP.2.E1

An undergraduate student is choosing between two career paths: medical doctor and chemist. The student expects that a chemistry major will prepare him for medical school and for a career as a chemist. But, if he chooses to be a doctor, he must also attend medical school after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry.

The undergraduate degree will cost $75,000. Medical school will cost an additional $300,000 (ignore the time value of money for this question). As a chemist, he expects his career earnings to be $1,250,000. As a medical doctor, he expects his career earnings to be $2,200,000.

Required

(A) According to relevant cost analysis, should this student produce a chemistry degree only or process his education further to produce a medical degree?

(B) Are there any strategic considerations that could affect this decision?

Answer (A)

The two alternatives to this problem are for the student to sell his labor accompanied by an undergraduate degree or to process his education further and sell his labor accompanied by a medical degree as well. (This is clearly not the complete universe of alternatives, but it is all we have to work with for this problem).

Given these two alternatives, we can ignore the cost of the undergraduate degree. That cost will be incurred for either alternative. The two alternatives only differ in whether they incur the extra cost of medical school and earn the extra income from being a doctor.

The medical school alternative costs an additional $300,000 and earns an additional $950,000 (i.e. 2,200,000 doctor’s earnings – 1,250,000 chemist’s earnings). Thus the net profit from getting a medical degree over a chemistry degree is $650,000. Medical school, from a relevant cost analysis perspective, is clearly the more profitable choice.

Answer (B)

There is relatively little strategic information in this problem. But we can make a few observations. First, this student has not yet earned his undergraduate degree. It is unclear if he is one month or four years away from earning it. The further out he is, though, the less reliable these numbers are (i.e. he may be at the wrong point in his career’s life cycle to make this decision effectively). Medical school will take several years beyond his undergraduate schooling too, which further weakens the certainty of his predictions. Similarly, a large proportion of his “career earnings,” especially as a doctor, are from later in his career when he has more experience, reputation, and connections. He is projecting earnings far into the future with this analysis. A lot can happen between now and then.

There are additional reasons he could reasonably question the medical school option. He has only, at most, attended undergraduate classes. He does not yet have first-hand experience taking medical school classes and may find them overly difficult. Furthermore, government health policy may be in flux, and many health policies impact doctors’ career earnings (i.e. the value chain within the medical field may change).

If any of these uncertainties is quantifiable, it could be included into the relevant cost analysis. Otherwise, he has to incorporate this uncertainty into strategic cost analysis. He would be wise to revisit this analysis several times along the road as he gains new information and as some of the uncertainty likely diminishes.

2GP.2.M1

A firm currently produces specialized industrial paint at a cost of $2.50 per gallon. and at a sales price of $5 per gallon. Sales volume is 100,000 gallons per period. The firm is considering processing this paint further into a more refined final product. The paint product is currently the subject of intense regulatory action from the national government, whereas the refined product would not be. The firm is confident that this refined final product would sell, at least, at a price of $200 per unit with 4,000 unit sales per period, although it could sell for much more.

To process the paint into the refined final product, the firm would need to lease equipment at a cost of $100,000 per period, and buy additional raw materials at a cost of $150,000 per period. It could use existing workers (i.e. idle capacity) as well as hiring two new workers at a cost of $35,000 per period.

(A) According to relevant cost analysis, how much money will the firm gain or lose by processing the paint further?

(B) According to strategic cost analysis, should the process the paint further or sell as is?

Answer (A)

The two alternatives are to sell the paint as is or to process it further into a more refined product. The $2.50 unit cost of producing paint is a joint cost and does not differ between alternatives. I will ignore it for this problem.

The sell alternative brings in

The process further alternative brings in

The process further option brings in $20,000 less than the sell option. Based on relevant cost analysis, the firm should sell the paint as is.

Answer (B)

This firm may be underestimating their revenues from the refined product. Perhaps this product is early in its life cycle and the potential for additional revenues as the product matures should be taken into account. Furthermore, the life cycle of the industrial paint product might be short, since regulation is driving it out of the marketplace. These two indicators both suggest that the firm should process further instead of selling

2GP.3 Keep-or-Drop

2GP.3.E1

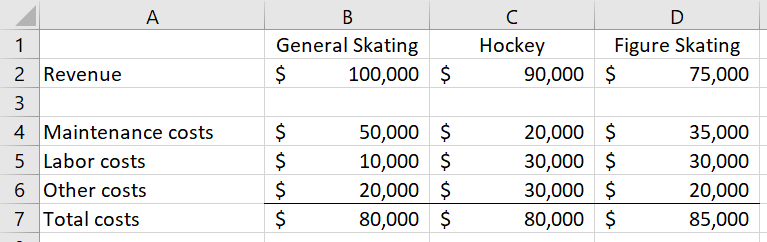

A Boise-area ice skating rink provides three products: general skating, hockey, and figure skating. The rink pursues a differentiation strategy through its variety of ice skating products. The rink’s motto is “Something for every member of the family.” The firm is deciding whether or not to drop figure skating. The three products have the following costs and revenues.

Required

(A) According to relevant cost analysis, should the firm drop figure

(B) According to strategic cost analysis, should the firm drop figure

Answer (A)

The two alternatives are (1) keep figure skating or (2) drop figure skating.

Keep:

General Skating: 100,000 – 80,000 = 20,000

Hockey: 90,000 – 80,000 = 10,000

Figure Skating: 75,000 – 85,000 = (10,000)

TOTAL: 20,000 + 10,000 + (10,000) = 20,000

Drop:

General Skating: 100,000 – 80,000 = 20,000

Hockey: 90,000 – 80,000 = 10,000

Figure Skating: 0 – 0 = 0

TOTAL: 20,000 + 10,000 + 0 = 30,000

Keeping figure skating is $10,000 less profitable than dropping it. Per relevant cost analysis, the product should be dropped.

Answer (B)

The firm’s differentiation strategy suggests the firm should keep figure

2GP.3.M1

Use the same revenue and cost data from problem 2GP.3.E1. But now consider that the firm believes dropping figure skating would reduce revenue for the other two products by 10% and that figure skating’s $20,000 of other costs are unavoidable.

Required

(A) According to relevant cost analysis, should the firm keep or drop the figure skating product?

(B) According to strategic cost analysis, should the firm keep or drop the figure skating product?

Answer (A)

The two alternatives are the same for this problem as 2GP.3.E1.

Keep:

General Skating: 100,000 – 80,000 = 20,000

Hockey: 90,000 – 80,000 = 10,000

Figure Skating: 75,000 – 85,000 = (10,000)

TOTAL: 20,000 + 10,000 + (10,000) = 20,000

Drop:

General Skating: (100,000 * 0.9) – 80,000 = 10,000

Hockey: (90,000 * 0.9) – 80,000 = 1,000

Figure Skating: 0 – (20,000) = (20,000)

TOTAL: 10,000 + 1,000 + (20,000) = (9,000)

It is now more profitable to keep the product than to drop it.

Answer (B)

No strategic information has changed since 2GP.3.E1, so the answer is the same: strategic cost analysis suggests to keep the product.

But, as a note, the new information about lost revenues and unavoidable costs is a sort of quantitative reflection of the firm’s qualitative strategy. This lost revenue reflects, at least partly, the differentiation that comes from the figure skating product line.