(Public domain images)

Chapter 2 Guided Practice Problems

2.1 Maximizing Profit and Decisions

2.1.1 What is a Decision?

I argued in Chapter 1 that cost accounting is the same as managerial accounting, and that both of these terms describe managers’ natural search for information that helps define the firm’s revenue function, R(∙), and cost function, C(∙). They want to define these functions better so they can better maximize profit.

How does this information help managers maximize profit?

Managers maximize profit by choosing the most profitable alternative from among two or more possible alternatives, on behalf of the firm’s owners. That is, they make decisions. Without more than one alternative, there is no decision to make and there is no way for a manager to maximize profit. Decisions are the fundamental unit of managers’ efforts to maximize profit.

Decision: a choice between two or more alternatives that lead to different R(∙) and/or C(∙).

And how can a manager know which alternative is most profitable? He or she can compare the firm’s R(∙) function and C(∙) function under each alternative. That allows one to calculate the π for each alternative (remember π is profit). Then just pick the alternative with higher π.

What if the R(∙) and C(∙) are the same for two alternatives? Then, from a profitability standpoint, they aren’t really two different alternatives. One could argue there’s no decision to be made at all because there is, effectively, only one possible profit outcome. Even the best manager only has a finite amount of time and cognitive ability to spend on each decision. Focusing on the profit differences of possible alternatives is necessary to ensure important decisions get made well.

2.1.2 Decisions in a Probabilistic World

Decision making in the real world is probabilistic. What I mean is that managers actually don’t know, for certain, if there are revenue or cost differences between alternatives. Not perfectly and ahead of time, anyway.

But even so, managers have some guesses about what revenue or cost differences there might be between alternatives. That is, they know something about the probability of differences between alternatives.

It’s fair, then, to say a decision is a choice between alternatives that one has reason to believe will lead to different revenue and/or costs.

For example, a manager might assign the accounting department to analyze two vendors, and it might turn out there’s no actual difference between them. My point is that a manager is unlikely to assign that analysis to the accounting department unless that manager has reason to expect

2.2 Relevant Cost Analysis

Deciding between alternatives based on their revenue and costs is called relevant cost analysis. Similar to what I said in Chapter 1, “cost” is in the name (relevant cost analysis) because cost differences are traditionally a key focus of this analysis. (But remember to still include revenue differences, too, or you can’t tell what each alternatives’ π is. Maximizing π is the objective of this analysis.)

This analysis is also called differential cost analysis, incremental cost analysis, and marginal cost analysis. All these terms mean the same thing as “relevant cost analysis.” Only revenue and costs that differ between two alternatives are relevant to deciding between those two alternatives, and the cumulative differences in revenue and costs between alternatives can be called the incremental or marginal effect of choosing one alternative over the other. All four terms are describing the same phenomenon. Remember, cost accounting is a relatively descriptivist field. We are sometimes inconsistent and redundant in our terminology. For

Below is an example of relevant cost analysis with two alternatives. Notice that each alternative has its R(∙), C(∙), and π. The far-right column shows the differences in R(∙), C(∙), and π between the two alternatives.

| Alternative #1 | Alternative #2 | Difference (#2 – #1) | |

| R(∙) | 1,000,000 | 1,250,000 | 250,000 |

| C(∙) | (500,000) | (775,000) | (275,000) |

| π | 500,000 | 475,000 | (25,000) |

Relevant cost analysis is easy once you have a table set up like this (most of the work is in building the table, as you’ll see). A manager simply picks the higher profit alternative based on the bottom row. Or, if you prefer, the bottom-right cell gives you the incremental effect of alternative #2: a loss of $25,000. Therefore alternative #1 is more profitable.

I’ll repeat that the difference in revenue and costs between the two alternatives is what leads to the decision. You could complete this analysis even if you could only see the far right column. In the interest of ensuring I do not miss something that differs between alternatives, I usually complete the whole table. Completing the whole table is sometimes called total cost analysis instead of relevant cost analysis because it can include irrelevant rows that do not differ between alternatives. In this

Relevant cost analysis, as a way of evaluating different alternatives and making decisions, is very flexible. It allows one to make good profit maximization decisions in an enormous variety of settings. Over time, though, a few common flavors of this analysis keep coming up. These are what I call traditional relevant cost analysis

2.3 Traditional Relevant Cost Analysis Decisions

2.3.1 Make-or-Buy

2.3.1.1 General Description

The first thing worth pointing out is that the alternatives for this traditional decision are given away in the name: alternative #1 is

Make-or-buy is a choice between the firm creating an input itself (make) or paying someone else for the input (buy). Often the input is a raw material input. For example, the car-maker General Motors (GM) used to have an internal division that made many of the parts for its own cars. That’s making. In the 1990s, that division was rebranded as Delphi and eventually it was spun off as a separate company, at which point GM shifted to buying those parts from the newly spun-off company.

But make-or-buy doesn’t have to be about a raw material. One can choose to make or buy labor or service (e.g. contractors versus permanent employees). Or one can choose to make or buy intellectual property (e.g. licensing software versus developing your own). This traditional decision works with just about any input a company uses.

2.3.1.2 Make-or-Buy Example

Below is a stereotypical make-or-buy decision. I assume sales dollars will be the same under both make and buy (more on this assumption in Section 2.4.3).

| #1: Make | #2: Buy | Difference (#2 – #1) | |

| R(∙) | |||

| Sales | 1,000,000 | 1,000,000 | 0 |

| C(∙) | |||

| Buy input | 0 | (500,000) | (500,000) |

| Equipment | (300,000) | 0 | 300,000 |

| Salaries | (225,000) | 0 | 225,000 |

| Miscellaneous | (50,000) | 0 | 50,000 |

| π | 425,000 | 500,000 | 75,000 |

In this example, I’ve assumed that buying the input means the company can avoid all equipment, facilities, and labor costs associated with making the input (this assumption does not always hold). Thus the buy alternative has a bunch of zeros in cells related to making the input internally. The make alternative, in turn, has a zero in the cell for the cost of buying the input externally. It looks like

2.3.2 Sell-or-Process-Further

2.3.2.1 General Description

This decision is closely connected to the make-or-buy decision. If the firm makes something instead of buying it, then the firm has two products: an input and a finished good. For example, GM produced Delphi car parts and then processed those car parts further, turning them into cars. It had two products: cars and car parts.

The two alternatives are again given away in the name of this traditional decision. Alternative #1 is to sell the input as just an input. Alternative #2 is to process the input further and sell it as a finished good.

This decision might be better called “sell-now-or-sell-later.”

2.3.2.2 Is There a Sell-or-Process-Further Decision?

A firm isn’t likely to have a sell-or-process-further decision if it never decided to make an input. But there are possible exceptions. For example, if a firm has unique access to a foreign market where it buys an input (instead of making it), then re-selling that input immediately in the domestic market might add enough value to prompt a sell-or-process-further decision.

The key here is that a firm only faces a sell-or-process-further decision when it adds value in some way to the input so as to create a meaningful market for that input (in addition to the market for the finished good). That value is usually added by making the input from scratch, but it doesn’t have to be.

This leads to an important rule of thumb: if there isn’t a market for both the input and the finished good, then there isn’t a sell-or-process-further decision to be made. Consider this sweet analogy.

Some people (“the smart ones,” I’ll call them) think cookie dough is as tasty as fully-baked cookies. As

such some of the cookie dough, i.e. the input, is consumed by the “market” for that input before being processed further into cookies, i.e. the finished good.In households where cookie dough is seen as a health hazard or is looked down upon as the crust of the ignorant masses, there is no market for the cookie dough input and thus all of the dough is processed further and made into finished goods: cookies. Those monsters!

As an example of how closely entangled this decision is with make-or-buy, remember that GM rebranded its car parts division as Delphi years before that division was spun-off. This rebranding, in large part, was aimed at boosting this division’s appeal to the external market for GM-made car parts. It made sense to sell some of those car parts on the external market rather than process them further into GM cars. The eventual decision to spin off Delphi meant the company would not earn profits from selling those car parts. The spinoff decision was as much about sell-or-process-further as it was a make-or-buy.

2.3.2.3 Additional Terms and Example

There are two additional terms that can be useful in this kind of decision: split-off point and joint costs. The split-off point is the point of development at which the input has an external market. The sell-or-process-further decision is a decision of whether to sell that input at the split-off point or to sell beyond the split-off point (i.e. after further processing).

Joint costs are costs incurred before the product arrives at the split-off point. Because these costs are incurred whether you sell at the split-off point or develop the product further, they are always irrelevant to your relevant cost analysis. The cost of making those Delphi parts (while it was still part of GM) was going to be incurred whether GM made those parts for sale on the external market or made them for use in GM’s own cars.

| #1: Sell | #2: Process Further | Difference (#2 – #1) | |

| R(∙) | |||

| Car part sales | 1,000,000 | 0 | (1,000,000) |

| Car sales | 0 | 10,500,000 | 10,500,000 |

| C(∙) | |||

| Joint costs (for car parts) | (500,000) | (500,000) | 0 |

| Equipment | 0 | (5,000,000) | (5,000,000) |

| Salaries | 0 | (4,250,000) | (4,250,000) |

| Miscellaneous | 0 | (500,000) | (500,000) |

| π | 500,000 | 250,000 | (250,000) |

The above table is an example of a sell-or-process-further decision. The part of the cost function that is associated with joint costs does not differ between alternatives. It could be ignored without affecting the quality of your relevant cost analysis. In this example, it makes more sense to sell the input on the external market than to process it further because that alternative has a higher π.

2.3.3 Keep-or-Drop

2.3.3.1 General Description

Keep-or-drop decisions come about when you decide whether to keep or drop a product line. The keep-or-drop decision is for multi-product firms. (Keep-or-drop decisions in single-product firms would be better called “going-out-of-business decisions”).

Alternative #1 is to keep selling the product line (i.e. the status quo). Alternative #2 is to drop it. Under ideal circumstances, these decisions are quite simple: if the product line has positive profits, it should be kept.

2.3.3.2 Complications for Keep-or-Drop Decisions

But the ideal circumstances are actually quite rare. Keep-or-drop decisions can get very complex. Here are two of the main complications that arise.

First, in a multi-product firm, dropping one product line probably affects the sales of other, related product lines. That is, product lines in a multi-product firm tend to be from the same family of products and have some interdependency. Interdependency is to how revenue and costs from one product line are affected by (i.e.depend on) the sales and costs of other product lines.

- If Apple, for example, suddenly stopped producing new iPhones, fees collected in their app store would be affected. If people are not buying new iPhones, presumably fewer apps would be developed and downloaded.

- If Pizza Hut stopped selling breadsticks, pizza sales would probably be affected because at least some people would order their pizzas elsewhere if they can’t get

breadsticks on the side. - If Deloitte suddenly stopped doing taxes, its audit sales might drop because some companies want their taxes and audit services performed by the same accounting firm.

Dropping one product line often affects related product lines’ sales, usually in the form of reduced revenues.

Second, some costs associated with a product line can’t be avoided just because a firm drops that product line. If Deloitte stops doing taxes, could it stop paying the salary of the administrative staff who help with tax work? Maybe. But some of those employees might fill dual roles, including roles required for the firm’s audit business. So, some of this labor cost can’t be avoided.

What about Deloitte’s software costs? It could avoid

2.3.3.3 Keep-or-Drop Example

The general rule of thumb is that keep-or-drop decisions initially (before considering complicating factors) favor drop more than they should (after complicating factors are accounted for). Look at the following table, where the firm is considering keeping Product PB while dropping Product J.

| #1: Keep | #2: Drop | Difference (#2 – #1) | |

| R(∙) | |||

| Sales – PB | 750,000 | 750,000 | 0 |

| Sales – J | 250,000 | 0 | (250,000) |

| C(∙) | |||

| Equipment – PB | (200,000) | (200,000) | 0 |

| Equipment – J | (200,000) | 0 | 200,000 |

| Salaries – PB | (40,000) | (40,000) | 0 |

| Salaries – J | (40,000) | 0 | 40,000 |

| Other – PB | (10,000) | (10,000) | 0 |

| Other – J | (20,000) | 0 | 20,000 |

| π | 490,000 | 500,000 | 10,000 |

Dropping Product J looks to be more profitable. However, that table fails to account for (1) decreased revenue in related product lines and (2) costs that can’t be avoided.

In the below table, I’ve revised the keep-or-drop decision. Now I assume that revenue for Product PB will likely go down by $50,000 if you drop Product J. (Since PB and J are related product lines.) I also assume $20,000 of salaries from Product J are unavoidable (assuming for example, that Product PB and Product J share some workers, so the firm has to keep those workers even if the firm stops selling Product J).

| #1: Keep | #2: Drop | Difference (#2 – #1) | |

| R(∙) | |||

| Sales – PB | 750,000 | 700,000 | (50,000) |

| Sales – J | 250,000 | 0 | (250,000) |

| C(∙) | |||

| Equipment – PB | (200,000) | (200,000) | 0 |

| Equipment – J | (200,000) | 0 | 200,000 |

| Salaries – PB | (40,000) | (40,000) | 0 |

| Salaries – J | (40,000) | (20,000) | 20,000 |

| Other – PB | (10,000) | (10,000) | 0 |

| Other – J | (20,000) | 0 | 20,000 |

| π | 490,000 | 430,000 | (60,000) |

Even though it initially looked like we should drop the product line, the second table clarifies that it actually is more profitable to keep the product line. That’s all because of the interdependency between the two product lines.

2.3.3.4 Add-or-Don’t Decisions

Without too much extra work, you can use your knowledge of keep-or-drop decisions to make the decision of whether to add a product line too. This would be an add-or-don’t decision.

The alternatives are adding the new product line or not adding it. Interdependency between different product lines’ revenue and costs are likely to play a role in this analysis too, although in the opposite direction. That is, revenue might increase in related product lines and some costs might overlap with other lines.

2.3.4 Special Order

2.3.4.1 General Description

A special order is a customer order that is “special” because it is out-of-the-ordinary and non-routine. These orders are usually high enough in volume to warrant special consideration by some form of manager or especially delegated decision-maker. They usually also involve a customer requesting a discount due to the size of the order. Special orders often arrive after the firm’s productive capacity has been planned and committed (which leads to the capacity constraint discussion below).

The firm that receives such an order has to decide just how special this customer is. Do they get their requested discount?

Sadly, a special order decision’s alternatives are not given away in its name. If so, it would be called an accept-or-reject decision because the choices are to accept the special order or reject it.

2.3.4.2 Special Orders with a Set Price

When the customer proposes a set take-it-or-leave-it price, special order decisions can be very simple.

But even special orders with a set price can get complicated by two types of costs.

- The cost of special one-time inputs required for the special order. These might be, for example, the cost of a special piece of equipment, a special license, or a special contractor.

- The cost of limited capacity. Remember that special orders usually arrive after capacity has been planned and committed. Accepting a special order often means not selling to regular-paying customers so as to make room for the special order. Lost money from those regular-paying customers is a cost of accepting the special order. (This cost is an opportunity cost. See Section 2.5.1).

2.3.4.3 Preview for Chapter 3

I discuss how to calculate the cost of limited capacity in Chapter 3. That’s because I need to talk about variable costs, fixed costs, and contribution margin (which are introduced in Chapter 3) before I talk about calculating the cost of limited capacity.

I imagine that you are already very familiar with those three terms: variable costs, fixed costs, and contribution margin. But I’ve intentionally delayed introducing them because I want to ground them in the theoretical framework set up in Chapters 1 and 2: firms making decisions to maximize profit. These three seemingly simple terms in cost accounting have a lot of theoretical depth to them. I think you might learn something new in Chapter 3 even if these terms are old hat to you.

In Chapter 3, I also discuss special orders in which a customer is negotiating the discounted price. Managers should know the ceiling and floor for special order prices before entering into those negotiations. I discuss price ceiling and floor calculations.

2.3.5 Overview of Traditional Decisions (Example Firm)

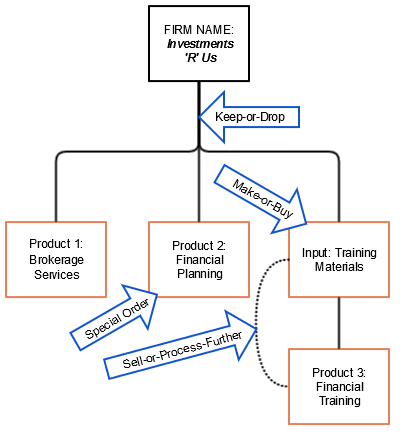

Below I have a diagram for a multi-product firm, Investments ‘R’ Us, which is making all four traditional decisions.

First, it is making a keep-or-drop decision about its brokerage services product. Because this decision affects multiple products and is affected by resources shared between products, I place this arrow at the neck of the chart, where all three products come out of. If it stops offering this service, that might negatively impact other products the firm offers. Also, shared resources between products might affect what costs are actually avoided by dropping this product.

Second, the firm is looking at a special order for its financial planning product. A local business wants the firm to provide financial planning services for its employees. It wants a discount. Accepting this offer will tie up the firm’s financial planners, affecting at least some of the regular business they are doing. Plus, the business uses a unique type of retirement planning software (i.e. a legacy system) and Investments ‘R’ Us would have invest a significant amount of time and resources training its planners on this software.

The third and fourth decisions are related to the firm’s financial training product. The firm currently licenses training materials from a local provider but is looking at the cost of bringing this in-house. This is a make-or-buy decision. But, going along with this decision is the possibility that the firm could then license some of its own training materials to an external market. This latter possibility involves a sell-or-process-further decision.

With the possible exception of special order decisions (which we will come back to in the next chapter), if I provided you with a fact pattern that details one of these traditional decisions, you should be able to complete the relevant cost analysis for them and provide the managers at Investments ‘R’ Us with the most profitable decision. This is an important skill for you to gain in a cost accounting class because these decisions come up again and again in business in one form or another.

2.4 Strategic Cost Analysis

2.4.1 What is Strategic Cost Analysis?

Managers pick the more profitable alternative in the relevant cost analysis table and, voilà, profit maximized. Right?

No, that’s just the start of the decision-making process. Managers then conduct

Some of the long-term profit effects for different alternatives are already included in regular relevant cost analysis. If the numbers are known or can be reasonably forecast, you would include them in the table. But if you stop there, your analysis will miss a lot of what drives long-term profit: customer value.

2.4.2 Customer Value and Strategy

Customers decide to buy a product because their benefit from that product is greater than the product’s cost. It’s a customer-centric version of the firm’s profit equation, but it uses different terms to avoid confusion: “customer value” instead of π, “customer benefit” instead of R(∙), and “customer cost” instead of C(∙). Customer value is the difference between (1) the customer benefit from the product and (2) the customer cost for the product. Customer value is also called the value proposition.

The key notion here is that greater customer value means stronger long-term viability for the firm and better outlook for future profits. Customer value, a key driver of long-term profits, gets missed in regular relevant cost analysis.

Strategy gurus say there are three main strategies for maximizing customer value: product differentiation, cost leadership, and focus. Product differentiation means increasing customer value by increasing customer benefit (while keeping customer cost from rising as quickly as customer benefit). Cost leadership means trying to increase customer value by decreasing customer cost (while keeping customer benefit from dropping as much as customer cost). Focus means increasing customer value by honing in on a specific customer class that either has a naturally high customer benefit or a naturally low customer cost for the product.

I have never been convinced there is a separate focus strategy. All companies have limits to their appeal and they focus on certain customers to one degree or another. I just cannot imagine a product aimed at every man, woman, and child on the planet. Maybe if the product were air. But even then some customers will want

So, as far as this textbook is concerned, there are only two mutually exclusive strategies: product differentiation and cost leadership. And these two strategies mean maximizing customer value by increasing customer benefit or decreasing customer cost, respectively. They’re mutually exclusive because you can’t pursue both of them at the same time.

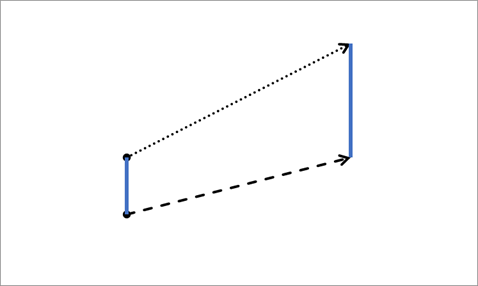

The figure below represents the product differentiation strategy. The top line is customer benefit and the bottom line is customer cost. The blue lines are customer value. A firm pursuing a product differentiation strategy will try to maximize customer value (which is supposed to increase long-term profit for the firm) by moving from the left to the right over time, increasing customer benefit faster than customer cost increases.

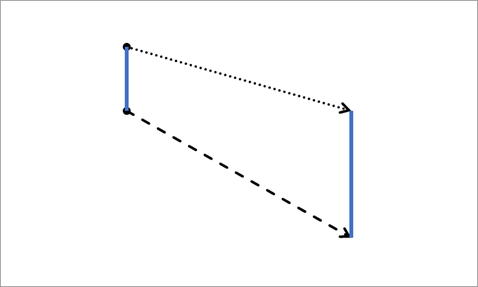

The below figure shows the cost leadership strategy. Firms pursuing this strategy will move from left to right over time, decreasing customer cost faster than customer benefit decreases.

To help me make my next point about customer value, I’m going to make an analogy between companies’ quest to maximizing customer value and mining for copper. A copper mining company doesn’t literally know how much copper ore is in the rock it can mine, but it has some educated guesses and can test some preliminary samples. It costs a lot to blast the rock and transport it and leach it and catalyze it, so the company uses its best guess to aim for rock that contains pockets of high-density copper ore.

Similarly, managers don’t exactly know what customers want, what tickles their fancy, what they value, or what they need. But they have some educated guesses. They aim their companies at pockets of customer value. Perhaps customers have an unmet need for a place to buy the lowest price groceries. They’re not too picky, and they want to save money. So Walmart aims at that pocket of untapped customer value with everyday low prices. Perhaps customers have an untapped need for an over-priced, I mean prestigious, smartphone. So Apple aims at that pocket of untapped customer value with the iPhone.

2.4.3 Strategic Issues Missed by Relevant Cost Analysis

Relevant cost analysis usually misses three aspects of strategic success, whether the strategy is product differentiation or cost leadership. That’s because customer benefit, customer cost, and the drivers of customer benefit and cost aren’t always financial. They can be hard to quantify and thus hard to include in a relevant cost

Strategy Driver #1: Product Life Cycles

Even the best products have a life cycle. They start out slow, ramp up, then eventually decline and die. Relevant cost analysis might suggest an alternative that is inappropriate for where the product is in its life cycle.

For example, analysis of a make-or-buy decision might recommend making an input for a product that is toward the end of its life cycle. This might be an inappropriate choice because it likely means a lot of unusable equipment or laid off employees when the product dies. The costs of unusable equipment and laid off employees, which can be harder to quantify, need to be considered as part of a manager’s strategic cost analysis.

Strategy Driver #2: Value Chain

There are internal and external value chains. Internal value chains are discussed a little more in Chapter 8. External value chains involve upstream suppliers and downstream distributors. Each link in the external value chain provides some part of customer value. Some parts of the value chain can be less visible to relevant cost analysis than others.

For example, it might seem more profitable for one firm to sell one of its inputs on an external market, given results from a sell-or-process-further relevant cost analysis. However, this move might compete with and hurt the sole supplier of a different input. Weakening this link in the value chain could have a very negative impact on long-term profits, exceeding any short-term improvement from selling rather than processing further.

I like the way this scene is filmed because it emphasizes that the information supporting this decision was literally sitting in the ledger the whole time (the accountant in me jumps for joy every time I hear that line: “June, grab the ledger, would you?”). But it was hard to quantify and analyze using traditional relevant cost analysis. It took someone looking at the ledger with an eye toward strategic cost analysis in order to properly interpret the situation and provide a very, very lucrative long-term insight.

Strategy Driver #3: Strategic Mismatch

Lastly, relevant cost analysis might suggest something that runs counter to the firm’s strategy. Whatever gains this analysis suggests in the short term need to be weighed against the long-term strategic implications, given that the chosen strategy reflects where management believes the greatest customer value is over the long term.

For example, a product differentiation strategy usually involves improving the perceived quality of the product in some way. This implies something for make-or-buy decisions. Making important inputs rather than buying them gives the firm more control over the quality of those inputs, thus potentially improving finished goods quality.

So a firm with a product differentiation strategy might, strategically, want to make most of its products’ important inputs, even if the make-or-buy relevant cost analysis suggests buying these goods is more profitable in the short-term. The firm is left to weigh between the long-term benefits of making the input against the short-term cost of choosing the “less profitable” make alternative (that is, “less profitable” according to relevant cost analysis).

2.5 Two More Cost Terms

2.5.1 Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost is the profit that could have been gained from alternative #1, which is lost when you choose alternative #2. This lost profit is considered an opportunity cost of choosing alternative #2: part of the price of choosing alternative #2 is the lost opportunity to pursue alternative #1. (Also the far right column in a relevant cost analysis table could be called the opportunity cost of choosing alternative #2 over alternative #1).

For example, college does not only cost the price of tuition, fees, room and board, books (well not in this case!), and so forth. College also limits your ability to work and earn money. Going to college comes at the expense of time working and dollars earned from that work. This lost income while going to school is part of the opportunity cost of going to college.

Get ready for some truth bombs about opportunity costs.

- Opportunity costs are the most obvious example of costs that are not expenses. Expenses are costs that get recognized on the income statement. Opportunity costs generally are not allowed on financial statements (a big no-no). The exception to this is some calculations related to the time value of money, which tries to account for some of the opportunity cost of some investments.

- Failing to account for opportunity costs can lead you to a decidedly wrong decision. Just ask Mark Zuckerberg about the opportunity cost of staying in school.

- On that topic, opportunity costs are incredibly context-dependent. Dropping out of college made perfect economic sense for Zuckerberg, who was sitting on a multi-billion dollar idea. But most people aren’t facing Facebook-level opportunity costs. Also, even Zuckerberg didn’t know, for sure, that things would pan out as they did.

- A lot of opportunity cost is strategic, sometimes lying in the long-term future. The further into the future, the less certain one can be. Opportunity cost arguments can be heavy with speculation and “gut feel.” This is all part of the messy strategic cost analysis process.

- Opportunity costs sometimes do not become apparent until one has completed relevant and strategic cost analysis. That’s one reason this chapter is so important and part of why I introduce it very early in the textbook.

2.5.2 Sunk Cost

A sunk cost is a cost that has been irreversibly incurred. Often a sunk cost is a cost in the past, but it doesn’t have to be. If it’s a future cost that is unavoidable, it’s also a sunk cost.

Sunk costs get a bum rap. The typical economic advice on sunk costs is simply: “ignore them!” I think that advice is literally true for relevant cost analysis, but I actually disagree with making it an absolute rule.

But before I tell you my thoughts, think about sunk costs for a minute. It’s obvious why the rule to always ignore them gets so much play in economics and business. Sunk costs can’t be avoided, so they literally can’t differ between alternatives. This means they’re never going to tip the balance in favor of a particular alternative in relevant cost analysis and are thus “irrelevant” by definition.

For example, assume a firm spends $10 million on a piece of equipment. Now the firm is unsatisfied with that equipment and is considering re-selling it. Unless a refund is possible, the $10 million purchase price is not relevant to the relevant cost analysis table. The firm bought the equipment for $10 million whether the firm re-sells it or not. That cost is sunk. The things that do differ between alternatives, and thus need to be in the relevant cost analysis table, are usually just the proceeds from re-sale and costs from lost productivity.

You know what? That’s a pretty compelling case. Maybe sunk costs should always be ignored.

Not so fast. This is where I explain why I don’t think ignoring sunk costs should be an absolute rule. Why was the $10 million piece of equipment purchased in the first place? Presumably the firm thought it was a worthwhile investment. Has that expectation materially changed? Or has the manager just forgotten why they thought it was a good investment in the first place?

See, managers are people (for now, anyway), and people sometimes suffer from thinking the grass is greener on the other side.

Sometimes human managers direct the firm to buy one software program then inexplicably change their mind and re-train everyone on a different software program a year later. Sometimes human managers leave supply chain commitments that have taken years to build because some upstart company has a cool-looking website. Sometimes human managers destroy decades of work building up a brand to chase after the shiny object of sub-branding.

If sunk costs help managers pause for a moment, helping the snap out of unprofitable course changes, then it might just be worthwhile to consider sunk costs.

So, even though I concede that sunk costs can’t be incorporated into managers’ relevant cost analysis, I think sunk costs can play an important role in managers’ strategic cost analysis. Managers who are reminded of the involved are likely to be more sober about irrationally breaking profitable commitments. Sunk costs, in short, could help convince them to not go chasing waterfalls.